Captain's Diary #52: Optimizations of vehicles and ocean

- Captain Marek

- Dec 10, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 12, 2025

Hello and welcome to the 52nd edition of Captain’s Diary. I am Captain Marek, and this week I will share some details about my recent work on optimizing vehicles and ocean simulation. This is a slightly more technical topic, so the TL;DR is that, due to complications with amphibious vehicles, we have optimized vehicles and the ocean simulation, and you will be able to enjoy 10-15% more FPS! Read on if you want to learn how these gains were achieved and why this has anything to do with amphibious vehicles.

Vehicles rendering

Vehicles in Captain of Industry are simulated in 2D. There are many reasons for this, mainly performance and implementation complexity (path-finding in 3D gets really hard, really fast). However, the game is in 3D, so each frame the height and 3D orientation of all vehicles has to be computed based on their 2D poses.

Vehicle pose computation is not particularly complicated:

Compute the 2D positions of four “corner points” of a vehicle based on its 2D pose (position and rotation). These four points are usually located where the wheels are, or where the tracks end.

Extend these 2D points to 3D by computing terrain height at each position. This also takes into account exceptions like vehicle ramps, where vehicles follow an alternative surface and not the terrain.

Fit a 3D plane through these points.

Compute a 3D pose (position and rotation) based on the final 3D plane.

The issue with amphibious vehicles

When we were implementing amphibious vehicles, one of the obstacles was the ocean, obviously! What I mean is actually being able to have the vehicles float on the waves. The thing is, our ocean is fully simulated on the GPU (more about this in CD #35), and the CPU does not know about the ocean surface at all.

There were two solutions on the table:

Download the generated ocean wave textures from GPU memory every frame and have the CPU compute ocean wave heights at the four corner points of each vehicle. This is quite easy to implement, but memory transfers from GPU to CPU have non-trivial cost, and the CPU work needed to actually compute the wave heights is significant (hundreds of instructions).

Have the GPU compute ocean wave heights at the vehicles' positions. The CPU would upload a list of the 2D points of interest to the GPU and a compute shader could then efficiently compute the corresponding ocean wave heights. This would be significantly faster than the previous solution.

Knowing that the first solution would mean significant additional CPU load, we had to opt for the second solution, so I jumped on it.

When I was writing the compute shader to evaluate wave heights, it struck me that we already have terrain height as a texture on the GPU for terrain rendering. Why not sample it too? And why not create another height texture for the special vehicle surface and sample that one as well? This would allow us to completely eliminate vehicle height sampling on the CPU.

And this is, folks, what we often call a “rabbit hole”. From a one-day task we suddenly have a one-week project!

But before I jumped into this rabbit hole, I did my homework and analyzed the performance of the vehicle pose computation on the CPU. I was thinking that if it took less than 1% of the sim update, it would not be worth optimizing. So I ran the analysis and, hold onto your hats, the vehicle pose computation took around 10% of the simulation time!

Seeing this result, it was clear to me that optimizing this code would be absolutely worth the extra effort. So I wrote the code to efficiently keep the vehicle surface texture on the GPU and use it, together with ocean and terrain textures, to fully resolve vehicle poses from 2D to 3D on the GPU. The final compute shader takes 2D poses and vehicle corner offsets for all vehicles and computes final 3D poses.

A benchmark showed that vehicle pose computation for 270 vehicles took around 1 ms, and now it is basically 0 ms on the CPU (just a memory copy of a small array).

And the best part is that computation of 200 poses on the GPU is so little work that we could be computing 10x more vehicle updates without slowing down, whereas the CPU would be linearly slower with each additional vehicle.

You may be wondering why the CPU would be so “slow”. Well, each vehicle samples four points, and each point needs four height samples for interpolation, that is 16 samples per vehicle. The vehicle surface is stored in a dictionary, so add 16 dictionary lookups and a bunch of ifs and method calls. Then there are trigonometric functions and many arithmetic operations. For 200+ vehicles, this adds up. There was no obvious inefficiency, just lots of memory lookups and math (I am pretty sure this was bottlenecked on memory).

It is fair to note that, due to CPU to GPU delays, vehicles are now a few simulation ticks behind. I have written a smart latency minimization system, so if your computer computes the results fast enough, the latency can be as low as one tick, and at worst it can be up to four ticks.

Ocean optimizations

Amphibious vehicles presented another problem with the ocean. Now that we could simulate vehicles “riding the waves”, we also have an option in the rendering settings to turn off the fancy simulated ocean and just use a plane with animated textures. The issue is that, while the animated textures give the low-fidelity ocean some depth, the 3D mesh is just a flat plane. Once you place vehicles on it, the depth illusion breaks and it looks like a flat surface.

So we had two options:

Just roll with it, it is a low-fidelity option anyway. Add a way to completely skip the wave computation in the compute shader that evaluates the vehicle poses.

Try to optimize the simulated ocean and remove the flat ocean option from the game.

Does this sound like a rabbit hole to you? A problem with potentially high complexity and uncertain results? Yeah, and what do we do before entering rabbit holes? Analysis! I wanted to know how much slower the simulated ocean is.

Based on my benchmarks, the simulated ocean took 10x more time per frame, and this could be even more on less powerful GPUs.

When I presented my findings in a meeting, and that I thought it was worth pursuing higher performance, Jeremy gently reminded me that my implementation of the ocean simulation could certainly be optimized further and gave me a few tips, so all hands on deck, we are going for option 2!

Now I don’t want to get too technical here, but I need to mention that our ocean uses what is called the inverse fast Fourier transform (IFFT) to simulate and sum hundreds of sine waves of various frequencies and amplitudes efficiently. It is the same tech they use in movies or so-called “AAAA” games, by the way.

IFFT has to be done in multiple stages, in our case 8, and my initial implementation invoked a compute shader for each stage. This is a natural thing to do, as each stage needs to end before the next one can begin. However, as Jeremy pointed out, these stages can be “fused” into one compute shader invocation. This is possible thanks to the GroupMemoryBarrierWithGroupSync function, which lets all threads in a thread group wait for each other so their intermediate results can be reused in the next stage. As you can imagine, synchronization of thread groups is way faster than invoking a new compute shader.

Fused IFFT kernels gave us a good 4-5x speedup, but I felt that we could still do better. My second target was to reduce the amount of work per frame. We were still doing four IFFTs per frame, which is a lot of work. My goal was to do the actual simulation less often and just use linear interpolation in between, basically the same thing we do for simulating the game, but for ocean waves.

I will spare you most of the technical details here, but I will mention that I have chosen to simulate the ocean 10 times per second and just interpolate in between. Implementation-wise we keep three sets of data: two that are being interpolated and a third that is being computed, and they rotate in round-robin fashion. Orchestrating all this was not trivial, but also not rocket science.

The biggest advantage of this technique is that individual IFFT computations can be invoked in different frames, further reducing per-frame load by 3-4x. What is even more awesome is that the more FPS you get, the less per-frame load there will be. For systems that run COI at 40+ FPS, there will be frames where no IFFT is even running on the GPU.

Here are the final benchmark results. Looking only at the GPU compute kernel load, the old IFFT was taking 0.8 ms per frame, and after all optimizations it is 0.05 ms per frame. That is a 16x speedup!

I tested this on an empty New Haven map, and the old flat ocean was giving me 352 FPS, the old fancy ocean was at 301 FPS, and the same ocean after optimizations was at 343 FPS. So the new ocean is not as cheap as the old one, but it is really close, so we decided to remove the old option from the game.

Final benchmark

To summarize, to get amphibious vehicles working we optimized vehicles pose computation and ocean rendering. On an end-game save from McRib with 270 vehicles the overall FPS went from 54.8 to 61.5, a 12% increase! Here are more detailed numbers:

Train waypoints

Lightweight train stations, also known as waypoints, are coming in Update 4! We heard your feedback that waiting bays and auxiliary stations that do not need loading modules take too much space.

A train waypoint works exactly the same as a station with regard to the train schedule, but no modules can be attached to it. However, it does not need any more space than the train track itself, so it can be built on parallel tracks without the need for extra spacing. Moreover, waypoints can even be placed on elevated tracks. The waypoint station will be available in the base game.

Nuclear locomotive

In the last Captain’s Diary I briefly mentioned that the upcoming Trains DLC will come with some new locomotives, and there was a lot of discussion about the spicy one - the nuclear locomotive. I have seen many speculations about how large it will be and whether it will need any fuel or water, so let me clear things up.

The nuclear locomotive is composed of three units: the crew car (unit A), the nuclear reactor and turbine car (unit B), and the condenser car (unit C). The entire locomotive is 25 tiles long (50 meters), equivalent to five tier 1 diesel locomotives.

The A unit carries a crew of two. Unit B houses the heavily shielded nuclear reactor and steam turbine that generates electricity for all driven axles. To make the locomotive self-sufficient without the need for water refueling, unit C is dedicated to condensing exhaust steam back to water that is fed back into the reactor.

Since the water is circulating in a closed loop, the only thing to refuel is the nuclear fuel. This is done by swapping the entire reactor. The kicker is that the reactor needs to be replaced only once every 100 years!

And if, for any reason, a 3-unit locomotive is not enough for you, it is possible to attach multiple B-C unit pairs after a single A unit.

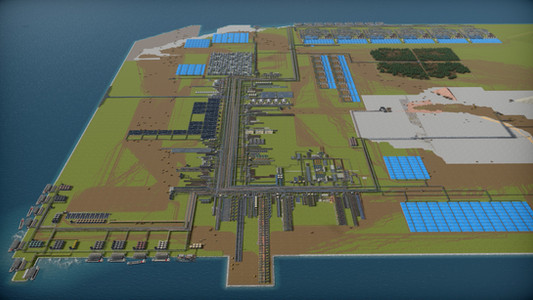

Community spotlight

In recent weeks I have seen people sharing their end-game factories over on our Reddit and Discord, and I wanted to shine a spotlight on some of them.

Reddit user Blackbird-234 shared their first rocket launch in the year 6379. This reminded me how diverse player playstyles can be. Their beautifully designed factory is almost emission free, most cargo is delivered by trains, and their sustainable mining practices left the mighty Golden Peak standing proud.

Reddit user Fickerra took another approach by building a modular mega-factory that uses a main bus to power 36 labs! Some say that main-bus-style logistics do not work in COI, and some feed 36 labs with it. I was looking for some save to do benchmarking and I think I have found it.

And last but not least, Discord user Tanakona has clocked in more than 2700 hours playing COI on Steam and has built a 100% self-sustaining colony on Dragontail Island. The unique twist is that instead of one huge city, they run five separate settlements with a total population of 12,600 workers and a fully operational level 3 space station. They also heavily rely on wood production (1500 per minute) and use steam trains as the primary means of moving goods.

Conclusion

And this concludes today's diary entry. We still have multiple job positions open, including audio/SFX, 2D art, and full-stack ASP.NET dev, so in case you or someone you know is interested, see our jobs page. Until next time, Captain Marek - out.